Spontaneous Generation

Aristotle (400 B.C) was one of the earliest recorder scholars to articulate the theory of spontaneous generation, the notion that life can arise from nonliving matter. He proposed that life arose form nonliving material if the material contained pneuma ("vital heat"). Even after single-celled organisms were discovered during the mid-1600s the idea of spontaneous generations continued to exist. Some scientists assumed that microscopic beings were an early stage in the development of more complex ones.

This theory persisted into the seventeenth century, when scientists undertook additional experimentation to support or disprove it. By this time, scientists waged an experimental battle over the two hypothesis that could explain the origin of simple life forms. Some tenaciously clung to the idea of abiogenesis (a= without, bio=life, genesis=beginning---beginning in absence of life), which embraced spontaneous generations. On the other side were advocates of biogenesis (beginning with life) saying that living things arise only form others of their same kind.

The proponents of the theory of spontaneous generation (abiogenesis) cited how frogs simply seem to appear along the muddy banks of the Nile River in Egypt during the annual flooding. Others observed that mice simply appeared among grain stored in barns with thatched roofs. When the roof leaked and the grain molded, mice appeared. Jan Baptista van Helmont, proposed that mice could arise from rags and wheat kernels left in an open container for 3 weeks. In reality, such habitats provided ideal food sources and shelter for mouse populations flourish.

One of the first people to test the spontaneous generations was Francisco Reddi, of Italy (1668) . He conducted a simple experiment in which he placed meat in a jar and covered in with fine gauze. Flies gathering at the jar were blocked from entering and thus laid their eggs on the outside of the gauze. The maggots subsequently developed without access to te meat, indicating that maggots were the offspring of flies and did not arise from some "vital force" in the meat. This experiment laid to rest that mice developed through abiogenesis, but did not convince many scientists.

Louis Jablot from France (1710) reasoned that even microscopic organisms must have parents, and his experiments with hay infusions (dried hay steeped in water) supported that hypothesis. He divided into two containers an infusion that had been boiled to destroy any living things: a heated container that was closed to the air and a heated container that was freely open to the air. Only the open vessel developed microorganisms, which he presumed had entered in air laden with dust.

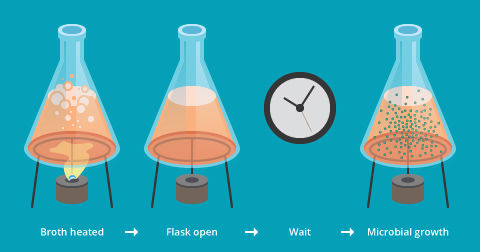

Jonh Needham an English priest (1745) reported the results of his experiments on spontaneous generation. Needham boiled mutton broth and then tightly stoppered the flasks. Eventually many of the flasks became cloudy and contained microorganisms. He thought organic matter contained a "vital force" that could confer the properties of life on nonliving matter.

A few year later the Italian priest and naturalist Lazzaro Spallanzi (1768) improved Needham´s experimental design by first sealing glass flasks that contained water and seeds. If the sealed flask were placed in boiling water for 3/4 and hour, no growth took place as long as the flask remained sealed. He proposed that air carried germs to the culture medium, but also commented that the external air might be required for growth of animals already in the medium. The supporters of the spontaneous generation maintained that heating the air in sealed flask destroyed its ability to support life.

Additional experiments further defended biogenesis. Franz Schulze and Theodor Schwann of Germany (1836) felt sure that air was the source of microbes and sought to prove this by passing air through strong chemicals or hot glass tubes into heath treated infusions in flasks. When the infusions again remained devoid of living things, the supporters of abiogenesis claimed that the treatment of the air had made it incapable of the spontaneous development of life.

Louis Pasteur (1864) to further clarify the air and dust were the source of microbes, he filled flasks with broth and fashioned their openings into long, swan-neck-shaped-tubes. The flasks openings were freely open to the air but where curved so that gravity would cause any airborne dust particles to deposit in the lower part of the necks. He heated the flask to sterilize the broth and then incubated them. As long as the flasks remained intact, the broth remained sterile; but if the neck was broken off so that dust fell directly down into the container, microbial growth immediately commenced. In another experiment Pasteur filtered air through three cotton plugs. He then immersed the plugs in the sterile infusions, demonstrating that growth occurred in the infusions from organisms trapped in the plugs.

John Tyndall (1876) delivered another blow to the idea of spontaneous generation when he arranged sealed flasks of boiled infusion in an airtight box. After allowing time for all dust particles to settle to the bottom of the box, he carefully removed the covers from the flasks. These flasks, too remained sterile. Tyndall had shown that air could be sterilized by settling, without any treatment that would prevent the "vital force" from acting.

Pasteur and Tyndall were fortunate that the organisms present in their infusions at the time of boiling were destroyed by heat. Others who tried the same experiments observed that the infusions became cloudy from growth of microorganisms. Now we know that heat-resistant or spore-forming microorganisms were responsible for the cloudy infusions, but at the time, the growth of such organisms was seen as evidence of spontaneous generation. Still, the works of Pasteur and Tyndall successfully disproved this theory. Recognition that microbes must be observed introduced into a medium before their growth can be observed paved the way for further development of microbiology- especially for the development of the germ theory disease.

References:

1.- K. Zwier. "Aristotle on Spontaneous Generation."

2.- Black, J. G., & Black, L. J. (2018). Microbiology: principles and explorations. John Wiley & Sons.

3.- Cowan, M. K. (2018). Microbiology: a systems approach. McGraw-Hill.

© 2020 by The Microbiology Post. Proudly created with Wix.com